EDITORIAL – The Good News Keeps On Coming

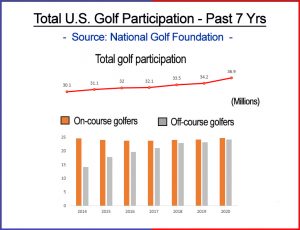

Golf saw a resurgence in 2020, and the numbers back that up. According to the National Golf Foundation (NGF), the total number of rounds played increased by 14% last year – a record one-year increase. As COVID-19 forced people to take inventory of their lives and with many indoor entertainment options shut down, golf became a beneficiary. Not only did beginners become fascinated with the game, but many people returned to the game after years-long absences.

Golf saw a resurgence in 2020, and the numbers back that up. According to the National Golf Foundation (NGF), the total number of rounds played increased by 14% last year – a record one-year increase. As COVID-19 forced people to take inventory of their lives and with many indoor entertainment options shut down, golf became a beneficiary. Not only did beginners become fascinated with the game, but many people returned to the game after years-long absences.

The NGF notes that the number of rounds played per year always fluctuates in the 2-3% range, mainly due to weather. So, a double-digit increase in rounds played, despite many courses being closed for months, means that once courses were open, it became hard to find a tee time at some places. And that’s a good thing! Teaching pros also took advantage of this surge in golfers as lesson books became filled. Anthony Benny, one of our fine members in Trinidad & Tobago, noted in the last issue of Golf Teaching Pro that his schedule is more filled than ever.

I know that where I teach, I have had no shortage of lesson-takers. Will the interest in golf continue? It will if the industry as a whole gladly welcomes all to play, and we as teaching professionals have an important role, too. Instead of saying the game is hard – how many times have we heard that? – we need to stress how fun it is to play. Our lesson programs can go a long way in retaining these players for the long haul.

By Mark Harman, USGTF Director of Education

To longtime USGTF teaching professional Matt Smith, there is no problem that cannot be overcome. Smith is one of the most accomplished teachers and players in USGTF history. He is well known for his prowess in these areas, but he has also drawn the admiration of everyone who knows him for overcoming stuttering.

” I have the passion that helps me to feel like every student is family. I have overcome a stuttering problem, and feel like I can motivate my students to overcome any issue,” said Smith. However, that does not define him. What does define him is the excellence he continually brings to any endeavor he attempts.

The owner of the Matt Smith Golf Academy in Pataskala, Ohio, Smith averages 55 lessons per week, has 150 kids ages 8-18 in his golf academy, and sends anywhere from three to 10 kids a year to play college golf. He is also a WGTF Top 100 Teacher and the first winner of the Harvey Penick Trophy for Excellence in Golf Teaching. He is a voracious reader and mentions he tries to get better as a player and a teacher every year.

“I feel at 45 years old I am a well-rounded player and teacher,” Smith remarked. “This allows me to work on every aspect of a golfer’s game. I do playing lessons and short game in season. I have all the latest technology to use indoors in the winter time. I am blessed that being a part of the USGTF helps me to achieve my teaching and playing goals every year.”

Smith has an Instagram account that can be accessed at

To longtime USGTF teaching professional Matt Smith, there is no problem that cannot be overcome. Smith is one of the most accomplished teachers and players in USGTF history. He is well known for his prowess in these areas, but he has also drawn the admiration of everyone who knows him for overcoming stuttering.

” I have the passion that helps me to feel like every student is family. I have overcome a stuttering problem, and feel like I can motivate my students to overcome any issue,” said Smith. However, that does not define him. What does define him is the excellence he continually brings to any endeavor he attempts.

The owner of the Matt Smith Golf Academy in Pataskala, Ohio, Smith averages 55 lessons per week, has 150 kids ages 8-18 in his golf academy, and sends anywhere from three to 10 kids a year to play college golf. He is also a WGTF Top 100 Teacher and the first winner of the Harvey Penick Trophy for Excellence in Golf Teaching. He is a voracious reader and mentions he tries to get better as a player and a teacher every year.

“I feel at 45 years old I am a well-rounded player and teacher,” Smith remarked. “This allows me to work on every aspect of a golfer’s game. I do playing lessons and short game in season. I have all the latest technology to use indoors in the winter time. I am blessed that being a part of the USGTF helps me to achieve my teaching and playing goals every year.”

Smith has an Instagram account that can be accessed at  He became the youngest winner on the PGA Tour in 82 years when he won the John Deere Classic in 2013, and quickly captured three major titles the next four years. Sustained stardom seemed certain for Jordan Spieth, but after winning The Open in 2017, he entered a slump that only now is he seeing signs that it may be behind him.

He became the youngest winner on the PGA Tour in 82 years when he won the John Deere Classic in 2013, and quickly captured three major titles the next four years. Sustained stardom seemed certain for Jordan Spieth, but after winning The Open in 2017, he entered a slump that only now is he seeing signs that it may be behind him.

Rafael Conde has been the president of the Mexican Golf Teachers Federation (MGTF) since its inception. Like many WGTF members, he came to golf from another career.

Prior to founding the MGTF, Conde served as a chemical engineer for companies such as Kimberley Clark and Frito Lay. He earned his Master Golf Teaching Professional certification in 1999 and at that point really got into teaching the game.

“Since then, I have been active as a golf teacher in Mexico, having the opportunity to certify many golf teaching professionals from all over the country,” said Conde. “Additionally, I am providing certification for caddies in many private golf clubs. Also, I hold a certification for consulting in agronomical treatment of golf course grass. This practice have offered me the opportunity to get in touch with golf club managers, greenskeepers and all personnel involved in the maintenance of golf courses.”

The MGTF has thrived under Conde’s leadership. The organization has made many inroads in the Mexican golf scene, and Conde plans to engage golf professionals who are not MGTF members to consider the benefits of certification. Conde notes that the upcoming year will provide a special challenge. “2021 is going to represent a special challenge due to COVID-19, but our efforts are going to be focused to promote certifications at all levels.”

Rafael Conde has been the president of the Mexican Golf Teachers Federation (MGTF) since its inception. Like many WGTF members, he came to golf from another career.

Prior to founding the MGTF, Conde served as a chemical engineer for companies such as Kimberley Clark and Frito Lay. He earned his Master Golf Teaching Professional certification in 1999 and at that point really got into teaching the game.

“Since then, I have been active as a golf teacher in Mexico, having the opportunity to certify many golf teaching professionals from all over the country,” said Conde. “Additionally, I am providing certification for caddies in many private golf clubs. Also, I hold a certification for consulting in agronomical treatment of golf course grass. This practice have offered me the opportunity to get in touch with golf club managers, greenskeepers and all personnel involved in the maintenance of golf courses.”

The MGTF has thrived under Conde’s leadership. The organization has made many inroads in the Mexican golf scene, and Conde plans to engage golf professionals who are not MGTF members to consider the benefits of certification. Conde notes that the upcoming year will provide a special challenge. “2021 is going to represent a special challenge due to COVID-19, but our efforts are going to be focused to promote certifications at all levels.”

For the past 10 years, we have featured a tour player each month in our USGTF e-newsletters. The USGTF has grown tremendously over these years and has developed many great teaching professionals in our ranks. For this reason, we will now be featuring one accomplished teaching professional in each monthly e-newsletter, as well. We started this in the February e-newsletter with USGTF member Michael Wolf. Now, it’s your turn. There are many of you who have incredible stories to tell, and if you’re wondering if we’re talking to you, the answer is yes! No matter what you have accomplished, rest assured others will find it of great interest. If you would like to tell the world about your experiences in being a USGTF member and a teaching professional – and why not? – in an upcoming newsletter, please contact the USGTF National Office at

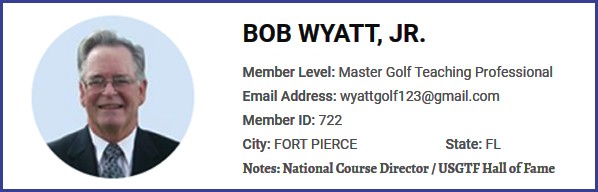

For the past 10 years, we have featured a tour player each month in our USGTF e-newsletters. The USGTF has grown tremendously over these years and has developed many great teaching professionals in our ranks. For this reason, we will now be featuring one accomplished teaching professional in each monthly e-newsletter, as well. We started this in the February e-newsletter with USGTF member Michael Wolf. Now, it’s your turn. There are many of you who have incredible stories to tell, and if you’re wondering if we’re talking to you, the answer is yes! No matter what you have accomplished, rest assured others will find it of great interest. If you would like to tell the world about your experiences in being a USGTF member and a teaching professional – and why not? – in an upcoming newsletter, please contact the USGTF National Office at  Are you looking to see if someone is a USGTF member in good standing? Now you can, online. On the homepage at USGTF.com, a Member Search feature has been added. When a member’s full name, as registered with the USGTF, is typed in, that member’s level of certification, member ID number, email address, hometown, and any pertinent notes about that member appear. Prospective employers and students now have a way to verify a person’s membership status through this feature. USGTF members in good standing are welcome to type their name in to verify that all information is correct.

Are you looking to see if someone is a USGTF member in good standing? Now you can, online. On the homepage at USGTF.com, a Member Search feature has been added. When a member’s full name, as registered with the USGTF, is typed in, that member’s level of certification, member ID number, email address, hometown, and any pertinent notes about that member appear. Prospective employers and students now have a way to verify a person’s membership status through this feature. USGTF members in good standing are welcome to type their name in to verify that all information is correct.

In 2003, the Australian Golf Teachers Federation made its appearance at the World Golf Teachers Cup, making a splash among member nations. In 2006, USGTF examiners traveled from the United States to Brisbane to conduct the first Master Golf Teaching Professional certification course in that country. After the retirement of AGTF president Gerry Cooney, the AGTF slowly began dissolving to the point that operations became dormant. However, talks with USGTF member Grant Garrison, who now lives in Australia, have commenced in regards to bringing the AGTF back to life. Garrison is also a PGA of America member who is a strong supporter of the USGTF and wants to revive the AGTF to head up future growth and development of the game in that country. Garrison is an accomplished teacher and experienced in the business of golf, and we look forward to a collaboration that benefits both Australian golf and the WGTF.

In 2003, the Australian Golf Teachers Federation made its appearance at the World Golf Teachers Cup, making a splash among member nations. In 2006, USGTF examiners traveled from the United States to Brisbane to conduct the first Master Golf Teaching Professional certification course in that country. After the retirement of AGTF president Gerry Cooney, the AGTF slowly began dissolving to the point that operations became dormant. However, talks with USGTF member Grant Garrison, who now lives in Australia, have commenced in regards to bringing the AGTF back to life. Garrison is also a PGA of America member who is a strong supporter of the USGTF and wants to revive the AGTF to head up future growth and development of the game in that country. Garrison is an accomplished teacher and experienced in the business of golf, and we look forward to a collaboration that benefits both Australian golf and the WGTF.